By Fiona Goldfinch August 2024

Cutting, micro-dosing, burning, poisoning, insertion… Chances are, if you work in education, health, or social care you will have heard some of these terms used to describe self-harm. And if you use the mental health charity Mind’s definition of self-harm which describes the practice as ‘hurting yourself’ (as opposed to physically injuring yourself) you have likely encountered friends and family members that have ‘indirectly’ self-harmed through behaviours such as eating disorders, substance abuse, and unsafe sex.

Self-harm is on the rise and statistics only show us the tip of the iceberg (Carr et al., 2016; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022). Most research that has been conducted is on people who seek medical support after self-harming, but many people don’t disclose self-harm or get medical help; it can be a very private and secretive activity. Some sources say as many as one in five young people will self-harm at some point (House, 2019; Parkinson, Thirlwall and Willetts, 2024), others are more conservative, estimating the number at one in ten (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2020). What we can be sure of is that more young people are self-harming than ever before (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022). The commonly held perception that teenage girls are most affected is an accurate one, however men of all ages are increasingly turning to self-harm and 25% of people that attend hospital after self-harming are over forty. The National Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (2014) found that incidents of self-harm in England rose by 167% between 2000 and 2014, with an increase in self-harming having been reported by men and women of all ages, from 16-74.

Risk Factors for Self-Harm

Age and sex aside, there is a plethora of other risk factors that may make someone more likely to self-harm including (but not limited to) being in prison, having peers or friends that self-harm and having experienced childhood neglect and/or abuse. Being neurodivergent or part of the LGBTQIA+ community means you are at higher risk, as does having serious physical or mental illness. Where you live is also a factor with “rates in Scotland having increased markedly relative to those in England” (Carr et al., 2016) and areas of high social and economic deprivation being disproportionately affected.

Why do people self-harm?

For those that have never felt the urge to hurt themselves, coming across someone that has done so, particularly if it is a loved one, can be baffling and distressing. It is important to understand that when people self-harm they are usually not intending to take their own life. Despite this, repeated instances of self-harm are the strongest predictor for suicide (Knightsmith, 2018) and the ‘more lethal’ the self-harm and the more times it occurs, the higher the risk. The reasons why people self-harm are deeply personal and as complex and different as the people themselves. Crucially, for some, self-harming works. It can become a coping mechanism and people that do it often report a ‘sense of relief’ (Wright et al., 2013). When we hurt ourselves, we release endorphins, hormones that act like natural opioids and help to relieve pain. This physiological response can contribute to self-harming becoming a habit, although it is worth noting that having self-harmed once, only “around a fifth (20%) of people do so again within a year” (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022). In a limited number of cases people have explained that it actually prevented them from taking their own life. While we may be aware of a likely reason for a person self-harming, it doesn’t pay to assume. The person themselves may not know or be able to articulate why they do it. Some common reasons are:

• the need to exert control,

• to cope with or to escape from overwhelming negative emotions or memories,

• into physical pain that distracts or is more easily managed,

• to punish themselves,

• to feel something when they experience a sense of numbness or disassociation,

• to have a reason to care for themselves, or have others care for them,

• they are ‘told to’ through intrusive thoughts or because they are experiencing psychosis.

Why are More People Self-Harming?

This question is more complex than it might appear at first glance, not least because there are cultural influences at play. Attitudes towards self-harm vary widely, as do the methods chosen; for example, a former mental health professional I spoke to mentioned that in her experience people that had been trafficked were more likely to set themselves alight than to demonstrate other methods of self-harm. Some have even suggested that self-harm may be prone to ‘fashions’. Many people cite social media as an inflammatory factor for the explosion in self-harm, but former mental health nurse Emma Lawson is surprisingly ambivalent, commenting: “I think it really goes two ways. On the one hand you’ve got people that as soon as it’s even mentioned on social media, are shouting very loudly that it’s just attention seeking (…) but then on the flip side there are some really good apps and websites out there that people can access. It’s just knowing where to look that’s the problem.” Given the pressure on mental health services and the waiting times for specialist appointments, online support could prove critical in filling the void. Whether the good outweighs the bad though, is open to debate. In the Netflix documentary ‘The Social Dilemma’ (2020) industry insiders are candid about the fact that social media algorithms drive users towards ever more extreme content and it is not difficult to find images of self-harm on the internet. Research also tells us that social media are linked to mental health issues (Karim et al., 2020). All things considered, it is hard not to conclude that social media does more harm than good, but could it be a symptom of a greater malaise? Society is changing and the things we used to turn to relieve stress may no longer be available to us. In his book ‘Lost Connections’ (2018) Johann Hari examines the impact of societal changes on our wellbeing; the conclusions he draws are significant and frightening. When everything around us is changing so fast, it could be argued that it is natural and normal that our responses to stress will also change.

Reacting to self-harm

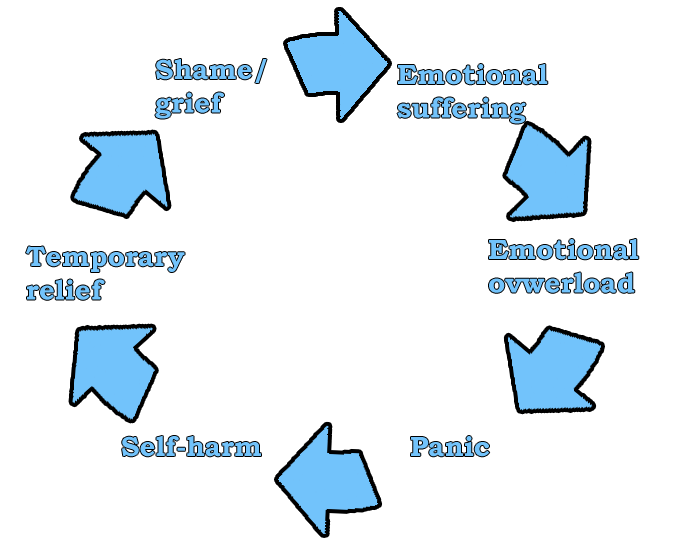

It can be tempting (particularly when faced with repeated instances of ‘superficial’ harming) to dismiss self-harming as attention seeking, but consider; how desperate or troubled does a person need to be to seek attention in this way? Surely if they are seeking attention, it is because they need attention? We all have our own bias and prejudice, whether acknowledged and challenged, or buried in our subconscious. Facing our own complex and challenging feelings around self-harm is vital if we are to understand the impact on the person concerned. Shame, guilt and grief often form part of a ‘self-harm cycle’, and our reaction can contribute to it, or mitigate it. We need to take time, be curious and listen to the person. Maintaining a calm, supportive and ‘matter of fact’ approach may help the person to confide further or ask for help. It is important to let the person say as much or as little as they wish; and to bear in mind that although they may benefit from therapy (which you could gently suggest) – you are not their therapist.

Getting Help

Not surprisingly, options for treatment usually revolve around dealing with the underlying issues that are causing the person to feel overwhelmed. Talking treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may help, however these can be prohibitively expensive if sought privately, or a very long time coming if provided by the national health service. For many, the urge to self-harm can be temporary – even fleeting, so techniques that help the person to ride the wave of emotion can be helpful; delaying, distraction and displacement are all examples of this. Completing a care plan and risk assessment is often a good place to start, but it is important to understand that it can be hard for the person to stop, and until alternative coping strategies are in place, they may not want to.

What Can We Do To Help?

• Educate ourselves. The more we understand about why people self-harm, the better.

• Examine our own beliefs about self-harm

• Listen to the person. Everyone who self-harms has a history and a reason.

• Signpost to support.

• Care for wounds to avoid infection and promote healing.

• Create a supportive environment, whether that be at home, work, or in an education setting.

• Be ready and willing to discuss practical strategies when the person Expresses that they want to stop self-harming.

• Look after ourselves, so we have the emotional resources we need to help the person who is self-harming.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, don’t despair. As self-harm increases, so does our knowledge, understanding, and capacity to affect positive change.

Sources of Information and Support

Books

• Understanding and Responding to Self-Harm: The One-Stop Guide, by Professor Allan House (2019).

• Can I Tell You About Self-Harm? By Pooky Knightsmith (2018).

• Self-Harm and Eating Disorders in Schools: A Guide to Whole-School Strategies and Practical Support, by Pooky Knightsmith (2015)

• When Teens Self-Harm: How Parents, Teachers and Professionals Can Provide Calm and Compassionate Support, by Monica Parkinson, Kerstin Thirlwall, and Lucy Willett (2024).

Websites/Apps

• www.selfharm.co.uk – Free online self-harm support for 10–17-year-olds. This Website introduces Alumina, online support groups for young people struggling with self-harm.

• www.calmharm.co.uk – Calm Harm is a free (in the UK) app that helps people manage or resist the urge to self-harm.

• www.youngminds.org.uk – Mental health charity for young people.

• www.mind.org.uk – Mental health charity for everyone.

• www.harmless.org.uk – Information regarding self-harm and suicide prevention.

• www.battle-scars-self-harm.org.uk – Support for people affected by self-harm.

Helplines

• Samaritans: call free on 116 123, 24 hours, 265 days a year.

• Shout: Free confidential 24/7 text messaging service for anyone who is struggling to cope.

Text “SHOUT” to 85258

• Childline: If under 19 call free on 0800 1111.

• Calm: The Campaign Against Living Miserably – a suicide prevention charity.

Call free on 0800 58 58 58 (for those age 15 or over).

References

• Battle Scars (no date) Support for Professionals. Available at: https://www.battle-scars-self-harm.org.uk/im-a-professional.html (Accessed: 29 July 2024).

• Carr, M. et al. (2016) ‘The epidemiology of self-harm in a UK-wide primary care patient cohort, 2001-2013’, BMC Psychiatry, doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0753-5.

• Cleveland Clinic (2022) Endorphins. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23040-endorphins (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

• House, A. (2019) Understanding and Responding to Self-Harm: The One-Stop Guide. London:

Profile Books Ltd.

• Iob, E., Steptoe, A. and Fancourt, D. (2020) ‘Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic’, The British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(4), pp.543-546. doi:10.1192/bjp.2020.130.

• Karim, F. et al. (2020) ‘Social Media Use and Its Connection to Mental Health:

A Systematic Review’, Cureus, 12(6), doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8627.

• Knightsmith, P. (2018) Can I Tell You About Self-Harm? London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

• Knightsmith, P. (2022) Why Do People Self-Harm? [Podcast]. 4th October. Available at: https://www.buzzsprout.com/1183931/11376141 (Accessed: 14 July 2024).

• Knightsmith, P. (2015) Self-Harm and Eating Disorders in Schools: A Guide to Whole-School Strategies and Practical Support. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

• Mental Health Foundation (2023) The Truth About Self-harm. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/publications/truth-about-self-harm (Accessed: 11 August 2024).

• Mind (2020) Self-harm. Available at: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/self-harm/about-self-harm/ (Accessed: 14 July 2024).

• National Institute for Care and Excellence (2023) Self-harm: How common is it? Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/self-harm/background-information/prevalence/ (Accessed: 14 July 2024).

• National Health Service (2023) Self-harm. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/feelings-symptoms-behaviours/behaviours/self-harm/ (Accessed: 14 July 2024).

• National Institute for Care and Excellence (2022) Self-harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng225/resources/selfharm-assessment-management-and-preventing-recurrence-pdf-66143837346757 (Accessed: 29 July 2024).

• Parkinson, M., Thirlwall, K and Willett, L. (2024) When Teens Self-Harm: How Parents,Teachers and Professionals Can Provide Calm and Compassionate Support. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

• Perry, B and Winfrey, O. (2021) What Happened to You? London: Bluebird.

• Royal College of Psychiatrists (2020) Self-harm. Available at: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/mental-illnesses-and-mental-health-problems/self-harm (Accessed: 14 July 2024).